story

Lest memory fade

A visit to Aljube Museum's permanent exhibition

Officially opened on April 25 of this year, the Aljube Museum is a tribute to resistance and freedom, championed by men and women who fought Salazar's dictatorship with incalculable sacrifices. The permanent exhibition is a place of memory, so that no future generation will forget the values of freedom and democracy.

Not much remains of the old Aljube Prison. In the 1960s, after several campaigns with international repercussion, Salazar’s dictatorship decided to close down this sinister prison establishment located in the heart of Lisbon. A thorough whitewashing operation erased everything that might recall the fascist government’s repressive character inside the building. It was not until almost half a century later that the old building – which had been a prison for centuries, and where many tears and blood were shed – opened to the public as a museum. A living museum with many memories that cannot and should not, for the sake of democracy, be forgotten.

A century with little freedom of the press

In the first decades of the twentieth century, the establishment of the Republic and WWI triggered a series of structural disruptions in Portuguese society which eventually led to the Military Dictatorship (1926-1933) and the Estado Novo regime (1933-1974). The 48 years that followed saw the gradual dissolution of the liberal state, of the multi-party system, of the right to unionize, and of freedom of the press, sentencing the country to an atrocious obscurantism that would only be broken by the 1974 military coup.

The beginning of this journey through Aljube Museum takes us to the interwar period in Portugal, with particular emphasis on the limitations to freedom of the press. According to the director of the museum, historian Luís Farinha, “the Portuguese 20th century was heavily marked by limitations to the freedom of the press. We must not forget that censorship was established as early as in the First Republic.”

There are numerous reproductions of censored documents, from newspaper covers to articles. The strength of the ‘blue pencil’ deprives citizens of knowledge and bare facts, and the press becomes a natural extension of the dictatorship’s interests.

Resisting and subverting the ‘indisputable truths’ of Salazar’s regime

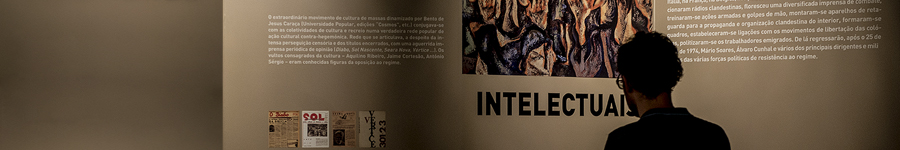

The underground press plays a key role in the opposition to Salazar and the strictures of censors. After walking through the lugubrious hallway of the Estado Novo’s ‘indisputable truths’ – ‘God, Fatherland, and Family’ -, a whole room is dedicated to the clandestine press, which, more than a mere propaganda instrument, was the sole vehicle for denouncing oppression and spreading information about the country and the world from unofficial points of view.

In addition to Avante!– the official newspaper of the Portuguese Communist Party-, visitors will find dozens of publications representing virtually all political trends in Portugal during the dictatorship’s 48 years, from radical left movements to far-right groups. Radio is also present, with broadcasts from the opposition’s radio stations, such as Portugal Livre [Free Portugal] or Voz da Liberdade [Voice of Freedom].

The photographic memory of the oppression and of the conditions under which clandestine meetings were held, articles were written, and underground newspapers were printed, extol the courage and ingenuity of those who dared to resist.

The prison’s ‘stalls’

The regime’s violent and oppressive nature materializes in its prisons, both in Portugal and in the overseas colonies. An ecclesiastical prison until the mid-nineteenth century, then a women’s prison, Aljube became a penal institution for the Miltary Dictatorship’s political and social prisoners in 1928 and was finally handed over to the political police as its prison of choice. Like other fascist prisons, Aljube bore the mark of the regime’s oppression and arbitrariness.

After long periods of interrogation, torture and humiliation, prisoners would arrive at the building, located on Augusto Rosa Street, where they would be locked up in the so-called stalls, or ‘drawers’. Originally, there were 14 of these dark, virtually airless one-meter-wide and two-meter-long cells. Four cells were rebuilt for the museum, where it is possible to experience the suffocating sensation prisoners felt even without entering those ‘stalls’.

In fact, it’s not easy to imagine what it would be like to be there, even for an hour, in complete isolation. Domingos Abrantes, a communist leader, was isolated in a stall for six months. Lino Lima, another prominent oppositionist, compared them to sarcophagi. The late MPLA leader Joaquim Pinto de Andrade described his experience to a Plenary Court in 1971, saying he had been “thrown into a narrow pen… where light and air entered through a 15-cm-wide and 20-cm-long opening, filtered through two iron doors and a hatch, which was permanently closed.”

Luís Farinha points out a curious fact: the cells are so small and claustrophobic that lamps on the ceiling tend to burn out in a few hours.

After the War, the Revolution

Colonialism and the anti-colonial struggle are the main features of the museum’s third floor. Salazar resists the unstoppable debacle of European empires by throwing Portugal into a war effort that marks the beginning of the end of the regime. From 1961 to 1974, a gagged country embarks on a war that would scar a whole generation of Portuguese and African young men.

Finally, April arrives. Preceded by a memorial (under construction) with the names of resistance victims – ‘Those whom we lost along the way’ – and by the epigraph ‘Democracy’, a room celebrates the ‘Captains’ and the April 1974 revolution. With an entire wall lined with red carnations.

A living museum of memories

Endowed with a documentation center that will offer a vast bibliographical and archival collection on various aspects of the resistance to the Estado Novo, the top floor of the museum features a pleasant cafeteria overlooking the river and a small auditorium.

According to the museum’s director, “starting in September, the auditorium will host several cultural initiatives. At the end of September we will launch the museum’s Gatherings, with talks by former political prisoners and film screenings. And in October, on Fridays, we will have a Protest Musicprogram, with performances by ‘baladeiros’.”

The Museum is still a work in progress. And it will continue to be so. According to Luís Farinha, “we want people who experienced the dictatorship to keep coming here and to enrich this collective museum with their own memories and collections.”

So that we don’t lose the freedom and democracy for which so many people fought.