The reeds which grow next to the mouth of Rio Seco, which flowed here and still runs underground, are at the origin of the name Junqueira. Used for the first time in an official document dating to the reign of D. Dinis, in which the monarch donates the lands of this site to the Abbess of the Monastery of Odivelas, D. Urraca Pais, it was to be fixed in the toponymy of the city in the 18th century. During this century there was a rush to the area by noble families who erected summer estates with sumptuous palaces that touched the river.

The journey through the aristocratic memory of Junqueira begins in the Palace of the Counts of Ribeira Grande, whose coat of arms decorates the façade. The palace, that was known by Liceu Rainha D. Amélia (D. Amélia Highschool), was built in the early 18th century by Francisco Baltasar da Gama, the Marquis of Nisa and descendant of Vasco da Gama. Bought later by the Count of Ribeira Grande, it suffered little damage in the Earthquake of 1755. It was inhabitated by the son of the count, D. Gonçalves Zarco da Câmara, the first Portuguese named to the Nobel Prize for Literature. Although altered quite a bit after being adapted to serve as a school in the decade of 1920, it retained the original features on the facade, the gardens and the chapel dedicated to Our Lady of Carmo. It awaits the beginning of the construction work that will transform it into a hotel and museum.

Beyond the crossroads of the Counts of Ribeira is Palácio Burnay, one of the most imposing buildings of this street. Classified as a Property of Public Interest, it is, in its current form, a 19th century building, but its origin goes back to the early 18th century when the brother of the Count of Sabugosa erected the house. Following the earthquake of 1755, it was bought by the Patriarch of Lisbon, D. Francisco de Saldanha, as a summer residence, being known thereafter, and for nearly a century, as Palácio dos Patriarcas. In the first half of the 19th century, it changed hands again, being acquired by Brazilian financier Manuel António da Fonseca, nicknamed Monte Cristo, who remodeled it to 19th century bourgeois taste. A few years later, this eccentric man, who was said to have drunk tea in gold cups, sold the palace to D. Sebastião de Bourbon, a prince from Spain and grandson of the King of Portugal, D. João VI. Alienated by his heirs, the palace was bought at an auction in 1879 by the Count of Burnay, who performed extensive renovations, in which artists such as Rodrigues Pita, Ordoñes, Malhoa and the Italians Carlo Grossi and Paolo Sozzi participated. After the count’s death, the Palace was purchased by the state from his widow, and several services were installed there. In recent years, it has hosted the Institute of Tropical Scientific Research.

Next to it stands the Palácio dos Condes da Ponte, the counts lived here until the end of the second quarter of the 18th century. The records say that after this period, it belonged to a member of the Posser de Andrade family, and that the apostolic nuncio Acciaioli, who had been expelled from Portugal in the time of the Marquis of Pombal, stayed here. In 1945, it was acquired by the Administration of the Port of Lisbon and underwent several more changes. Outside, its garden and fence were partially demolished when the Instituto de Higiene e Medicina Tropical and some pavilions of the Egas Moniz Hospital were built.

The Palácio Pessanha Valada, next to the stream, is named after two of its owners: D. João da Silva Pessanha, responsible for its construction after the earthquake of 1755, and the 2nd Marquis of Valada, D. José de Meneses da Silveira e Castro, Peer of the Kingdom of the Council of D. Luis, and chief officer of the Royal House, a man known for his intelligence and erudition. In front of this house, there was an old fort, which was turned into a prison in the reign of D. José where the Marquis de Alorna and Father Malagrida were imprisoned. It was demolished in 1939 during the works for the Portuguese World Exhibition.

After the Egas Moniz Hospital, the journey is interrupted by the beginning of Calçada da Boa Hora, where the Palácio is located. Its history is linked to the apogee and decadence of the Saldanha family. The primitive building, dating from the 16th century, underwent thorough renovations in the 18th century, when the 2nd Count of Ega, Aires José Maria de Saldanha, was the owner. The magnificent Salão Pompeia (Pompeii Hall), lined with panels of Dutch tiles representing views of European ports, is from his time and is now classified as Property of Public Interest. At the time of the French Invasions, this house experienced days of glory with parties promoted by the Count, in which General Junot was a frequent guest. The friendship with the invaders led the family into exile, and the Palácio served first as a hospital and then as Marshal Beresford’s headquarters, being eventually donated to him by D. João VI, 1820. Three years later, the Saldanha family rehabilitated and demanded the property back. However, they would not be able to maintain it. It was sold and passed through several owners until it was acquired by the State in 1919, that here installed the Historic and Colonial Archive (today Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino).

An extensive wall bordered by trees accompanies the return to Rua da Junqueira. The wall surrounds Quinta das Águias, the magnificent set of the 18th century that today is abandoned, although classified as Property of Public Interest. The origin of this farm goes back to 1713 when a lawyer from the Casa da Suplicação built a palace here. The property was sold in 1731 to Diogo de Mendonça Corte-Real, Secretary of State in the reign of João V, who undertook great works in it, probably under the responsibility of Carlos Mardel, to whom he was close. Diogo Corte-Real was exiled by the Marquis of Pombal and never returned to Junqueira. After his death in 1771, a long dispute between his heirs and the Holy House of Mercy, to whom the former secretary had left his property, led to the abandonment and ruin of the farm. In 1841, it was bought by public entrepreneur José Dias Leite Sampaio who rehabilitates it, presumably with a project by Italian Fortunato Lodi. After his death, Quinta das Águias, which owes its name to the two large stone eagles that flanked the gate, passed through several owners, among them Dr. Fausto Lopo Patrício de Carvalho, who between 1933 and 1937 carried out deep renovations with the help of architects Vasco Regaleira and Jorge Segurado. Currently, the palace, which has been ransacked and vandalized several times, is on sale.

A few steps ahead, in a recess of the street, the colorful Junqueira Fountain demands a stop. Built in 1821, under the design of architect Honorato Macedo e Sá, it started operating the following year. Initially fed by a water mine located in Alto de Santo Amaro, from 1838 onward it began to be fed by a new source near Rio Seco. The current arrangement is by Raul Lino who ordered reproductions of rococo tiles to be put in place. In front, the rear of the Cordoaria Nacional, a building that extends for about 400 meters, was one of the first industrial centers of Junqueira. Created in the 18th century by decree of the Marquis of Pombal, it produced cables, candles, fabrics and flags.

Some doors above, one of the most remarkable buildings of Junqueira is to be found, the House of Lázaro Leitão Aranha, where today the Lusíada University is located. Built in 1734 by this important figure of the reign of King João V, who delivered the work to Carlos Mardel, this house welcomed illustrious tenants like Prince Charles Mecklenburg, brother-in-law of the King of England. It was also the scene of scandals such as the kidnapping of D. Eugenia José de Meneses, carried out in 1803 by the court doctor, João Francisco de Oliveira. There are suspicions this was ordered by prince D. João, the true seducer. The Palace went through several owners who carried out works by architects such as Korrodi, Bigaglia, Francisco Vilaça and Raul Lino. In one of these campaigns, the chapel, dating back to 1740 and dedicated to Our Lady of Conceição, was converted into a stable, and the original tiles were covered by masonry walls.

On the way to the last point of the route we can see, on the left, two Art Nouveau houses with facades embellished with decorative arches and forged iron balconies. Opposite the Palace of the Marquis of Angeja, in the square with the same name, we return to the 18th century. After seeing his house destroyed in the earthquake of 1755, the marquis, D. Pedro António de Noronha e Albuquerque, received the land in Junqueira from the crown to build a new house, where there had previously been a fort. It is said that D. José I took refuge here after the attack against him in 1758. The palace remained in the possession of the Angeja family until 1910, when it was bought by the merchant José Alves Diniz that transformed it into a renting building, having as tenants illustrious figures such as Bernardino Machado and Almeida Garrett. In the west wing of the Palace, where a school operated, the Municipal Library of Belém has been installed since 1965.

Let’s start at the end, as if we were suggesting an itinerary to celebrate Ingmar Bergman’s 100 years. And ‘at the end’ means (re)discovering the Swedish filmmaker’s final work – Saraband(2003). At Cinema Ideal from July 12 onward, Liv Ullmann and Erland Josephson return to the silver screen to revisit, 30 years later, the characters from Scenes from a Marriage (1973). The two Bergmanian actors are joined by Borje Ahlstedt and Julia Dufvenius to interpret – in the words of Bergman himself – “a concert for symphony orchestra with four soloists.” A magnificent, innovative work in the use of digital cameras, Saraband’s return coincides with Bergman’s birthday on July 14.

And on the same day the Portuguese choreographer Olga Roriz will showcase A Meio da Noite (In the Middle of the Night) at Festival de Almada. According to Roriz, this work addresses “Bergman’s existentialist themes, and it is also a piece about the creation process, in a relentless search for oneself and others.” Touring in Portugal and Brazil, A Meio da Noite will be staged at Teatro Camões in October.

Back to Bergman’s oeuvre, key titles from his filmography will also be screened in October – not only in Lisbon but also around the world (just have a look at the Ingmar Bergman Foundation webpage to gauge the magnitude of the event). At Espaço Nimas, besides absolute masterpieces like The Seventh Seal or Persona,which have been regularly screened in that venue over the past few years, this new cycle includes three ‘new’ titles: Hour of the Wolf,, Shame (both released in 1968) and The Passion of Anna (1969), films that had not yet been included in the extensive catalog of Leopardo Filmes, the company that distributes and publishes Bergman’s films in Portugal.

In addition to his oeuvre, Espaço Nimas will also screen two documentaries focusing on the Swedish master’s unique personality. In Bergman – A year in a life,Jane Magnusson revisits the pivotal year of 1957, when The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries earned him international acclaim as a major filmmaker; when he made his first TV movie; and when he directed several theatrical productions, including a 5-hour rendering of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt. According to Variety,Magnusson’s documentary is a striking portrayal of “a man so consumed by work, and by his obsessive relationships with women, that he seemed to be carrying on three lives at once.”

The second film to be premiered is Searching for Ingmar Bergman,by Margareth von Trotta (director of Hannah Arendt). In this documentary, the German filmmaker sets out to trace Bergman’s legacy by compiling interviews with directors who have been “touched” by the master, such as Olivier Assayas, Ruben Östlund, Mia Hansen-Love and Carlos Saura; screenwriters and playwrights, such as the great Jean-Claude Carrière; and actors, such as Liv Ullmann.

And to close this “itinerary,” a complementary suggestion: Bergman’s autobiography The Magic Lantern,published in Portugal as A Lanterna Mágica (Relógio d’Água). Here the filmmaker wrote: “Film work is a powerfully erotic business; the proximity of actors is without reservations, the mutual exposure is total. The intimacy, devotion, dependency, love, confidence and credibility in front of the camera’s magical eye… the mutual drawing of breath, the moments of triumph, followed by anticlimax: the atmosphere is irresistibly charged with sexuality. It took me many years before I at last learned that one day the camera would stop and the lights go out.”

Ingmar Bergman was born on July 14, 1917, in Uppsala, a small town north of Stockholm. The son of a Lutheran pastor, his oeuvre was indelibly marked by his rigid, austere education. He became interested in theater as a student at Stockholm University (he wrote his first play, The Death of Kasper, in 1941). Cinema came afterwards – his first script was written for Alf Sjöberg’s Torments (1944). His directorial debut would take place the following year, with Crisis. Subsequently, Bergman built a long career in theater and film, and was globally acclaimed as one of the most brilliant authors of our time. He died in Fårö Island on July 30, 2007.

Not much remains of the old Aljube Prison. In the 1960s, after several campaigns with international repercussion, Salazar’s dictatorship decided to close down this sinister prison establishment located in the heart of Lisbon. A thorough whitewashing operation erased everything that might recall the fascist government’s repressive character inside the building. It was not until almost half a century later that the old building – which had been a prison for centuries, and where many tears and blood were shed – opened to the public as a museum. A living museum with many memories that cannot and should not, for the sake of democracy, be forgotten.

A century with little freedom of the press

In the first decades of the twentieth century, the establishment of the Republic and WWI triggered a series of structural disruptions in Portuguese society which eventually led to the Military Dictatorship (1926-1933) and the Estado Novo regime (1933-1974). The 48 years that followed saw the gradual dissolution of the liberal state, of the multi-party system, of the right to unionize, and of freedom of the press, sentencing the country to an atrocious obscurantism that would only be broken by the 1974 military coup.

The beginning of this journey through Aljube Museum takes us to the interwar period in Portugal, with particular emphasis on the limitations to freedom of the press. According to the director of the museum, historian Luís Farinha, “the Portuguese 20th century was heavily marked by limitations to the freedom of the press. We must not forget that censorship was established as early as in the First Republic.”

There are numerous reproductions of censored documents, from newspaper covers to articles. The strength of the ‘blue pencil’ deprives citizens of knowledge and bare facts, and the press becomes a natural extension of the dictatorship’s interests.

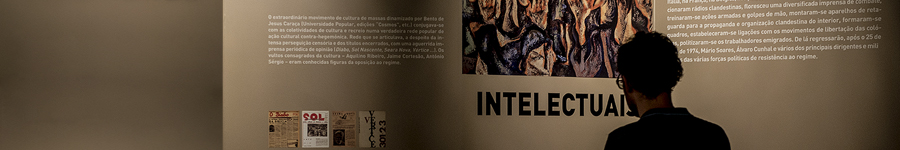

Resisting and subverting the ‘indisputable truths’ of Salazar’s regime

The underground press plays a key role in the opposition to Salazar and the strictures of censors. After walking through the lugubrious hallway of the Estado Novo’s ‘indisputable truths’ – ‘God, Fatherland, and Family’ -, a whole room is dedicated to the clandestine press, which, more than a mere propaganda instrument, was the sole vehicle for denouncing oppression and spreading information about the country and the world from unofficial points of view.

In addition to Avante!– the official newspaper of the Portuguese Communist Party-, visitors will find dozens of publications representing virtually all political trends in Portugal during the dictatorship’s 48 years, from radical left movements to far-right groups. Radio is also present, with broadcasts from the opposition’s radio stations, such as Portugal Livre [Free Portugal] or Voz da Liberdade [Voice of Freedom].

The photographic memory of the oppression and of the conditions under which clandestine meetings were held, articles were written, and underground newspapers were printed, extol the courage and ingenuity of those who dared to resist.

The prison’s ‘stalls’

The regime’s violent and oppressive nature materializes in its prisons, both in Portugal and in the overseas colonies. An ecclesiastical prison until the mid-nineteenth century, then a women’s prison, Aljube became a penal institution for the Miltary Dictatorship’s political and social prisoners in 1928 and was finally handed over to the political police as its prison of choice. Like other fascist prisons, Aljube bore the mark of the regime’s oppression and arbitrariness.

After long periods of interrogation, torture and humiliation, prisoners would arrive at the building, located on Augusto Rosa Street, where they would be locked up in the so-called stalls, or ‘drawers’. Originally, there were 14 of these dark, virtually airless one-meter-wide and two-meter-long cells. Four cells were rebuilt for the museum, where it is possible to experience the suffocating sensation prisoners felt even without entering those ‘stalls’.

In fact, it’s not easy to imagine what it would be like to be there, even for an hour, in complete isolation. Domingos Abrantes, a communist leader, was isolated in a stall for six months. Lino Lima, another prominent oppositionist, compared them to sarcophagi. The late MPLA leader Joaquim Pinto de Andrade described his experience to a Plenary Court in 1971, saying he had been “thrown into a narrow pen… where light and air entered through a 15-cm-wide and 20-cm-long opening, filtered through two iron doors and a hatch, which was permanently closed.”

Luís Farinha points out a curious fact: the cells are so small and claustrophobic that lamps on the ceiling tend to burn out in a few hours.

After the War, the Revolution

Colonialism and the anti-colonial struggle are the main features of the museum’s third floor. Salazar resists the unstoppable debacle of European empires by throwing Portugal into a war effort that marks the beginning of the end of the regime. From 1961 to 1974, a gagged country embarks on a war that would scar a whole generation of Portuguese and African young men.

Finally, April arrives. Preceded by a memorial (under construction) with the names of resistance victims – ‘Those whom we lost along the way’ – and by the epigraph ‘Democracy’, a room celebrates the ‘Captains’ and the April 1974 revolution. With an entire wall lined with red carnations.

A living museum of memories

Endowed with a documentation center that will offer a vast bibliographical and archival collection on various aspects of the resistance to the Estado Novo, the top floor of the museum features a pleasant cafeteria overlooking the river and a small auditorium.

According to the museum’s director, “starting in September, the auditorium will host several cultural initiatives. At the end of September we will launch the museum’s Gatherings, with talks by former political prisoners and film screenings. And in October, on Fridays, we will have a Protest Musicprogram, with performances by ‘baladeiros’.”

The Museum is still a work in progress. And it will continue to be so. According to Luís Farinha, “we want people who experienced the dictatorship to keep coming here and to enrich this collective museum with their own memories and collections.”

So that we don’t lose the freedom and democracy for which so many people fought.

paginations here