Is his work closely linked to the academic world?

I am also an architect in the traditional sense of the word. I have a studio in Paris, where I am a teacher, as well as in Lausanne (Switzerland) and Harvard (USA). About half of my time is devoted to teaching and the rest to my studio. In addition, I write books and articles on contemporary architecture subjects.

This edition of the Triennale has as its central theme ” A Poética da Razão” (The Poetics of Reason). Were Eric Lapierre and his team the ones who chose it?

It is a work I have been developing with a team of professors with whom I collaborate in the school of architecture (École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires à Paris-Est). We had been working on the subject for about a year now in the academic field. The Poetics of Reason is a research project that seeks to define the specifics of the rationality of architecture. The invitation was made official about three years ago, at the end of the previous (2016) Triennial. This allowed us to have all this time to work on the subject, a period of time that allows us to research deeper, unlike other biennials where you only have six months of preparation, for example.

How do you characterize this rationality?

For our team it is important to clearly state that creation is part of intuition, but it is also based on rationality. Architecture is a public art; its works are not enclosed in museums or private collections. They belong to everyone, not just the architect or his clients. They are part of the public space and the city. Thus, it is important to state that architecture must be rational, intelligible and understandable to all, and that in order to achieve this purpose it must be based on rational premises. Note that when I refer to rationality, it is not that it is more boring than something more subjective. Architecture always has a subjective aspect, but this part doesn’t have to be the most relevant. It is important to think that the reason is glamorous. And that it involves a lot of imagination.

Aren’t these concepts usually classified as antagonistic?

There is no opposition between rationality and sensibility or sensuality and imagination. One of our exhibitions, Interior Space,curated by Fosco Lucarelli and Mariabruna Fabrizzi, is about imagination in architecture. It shows that an architect must start by creating his own imagination as a corollary of a rational process. It should go beyond taste: architects need more solid reasons to act and to judge things. For the public, appreciation has to do with everyone’s taste, which is natural. For an architect, like an artist, there is a rational process in the imagery that comes from the memory, the classifications, the choice of field, or the tradition in which the creator would like to inscribe his work. These aspects belong to a process of rationality that is neither dry or boring, nor any less interesting than creativity. There is a bridge between rationality and creativity that is impossible to destroy. Rationality is a way of inscribing our obsessions or deliberations in the field of common culture. It is the mediator between these intimate obsessions and the common culture.

Is it a tool?

Yes, a tool, an interpretation and reading network. Something that opens up the imagination.

How does this relate to individuality? For example, with the renowned architects who have a very recognizable style?

You are talking about starchitects [“stars of architecture”]. There are some here in Portugal, such as Siza Vieira. These are people who have developed a personal view of architecture throughout their career. These architects are keenly aware of the weight of their culture and, for this reason, their works are easily appropriated by the public. For me, the point of the discipline of architecture is also to emphasize that being an architect is to be involved in this culture. It is the fact that you consciously inscribe your work in the flow of architectural culture that allows collective things to happen. It is much bigger than an individual. To make architecture is to do something collective, even if it is a private house: it is always collective because it belongs to the common culture of architecture.

The names of the Triennale exhibitions suggest that ” Natural Beauty ” and ” Inner Space ” are from a more interior universe and that ” Economy of Means and Arquitecture and Agriculture: In the Side of the Field” are from a more rational universe.

I wouldn’t say so because we try to define the specifics of the rationality of architecture and all this rationality is essentially based on “Economia de Meios” (Economy of Means). The other exhibitions address specific aspects of the rationality of architecture. “Beleza Natural” (Natural Beauty) It’s about the fact that we need a structure for a building to stand up. It is about the choices one can make to design a structure.

Can you specify?

Consider, for example, a branch of a tree. It has the shape and amount of material just enough to balance itself. This quality can be replicated in building structures, for example, to cover the greatest amount of space with as little material as possible. Economy of Means is a way of thinking that is closely linked to natural processes. Inner Space deals with the brain of the architect and how the architect uses rational processes to build his imagination. It uses models, drawings, virtual reality and a series of objects that are a kind of cabinets of curiosities. Agriculture and Architecture addresses the environment and the problems we are currently experiencing like global warming. The exhibition evokes the history of the environment and proposes four scenarios for the near future. It is a way of alerting the public that we must change dramatically and soon. And that we need architecture for that. Architecture has always responded to contemporary social issues. When we pass through a crisis it can be very easy to say that we don’t need architecture, but if tomorrow the environment is bad, ugly and people are depressed, we need to have solutions.

I believe you can mobilize your students with these questions, but how can we raise awareness among the public authorities, our leaders?

Certainly our leaders are not yet ready, but there has been an evolution. Ten years ago, only the ecological parties were talking about these issues. Today, with the exception of some extremist figures, such as Trump or Bolsonaro, any reasonable political leader addresses these issues. I do not think they can already make the right decisions because the necessary measures would be difficult to explain to the populace. In the near future, this will be one of the central questions: how will we be able to impose the necessary changes on those who have become accustomed to live wasting energy and resources.

Do you think there is a responsibility of architects to deliver this message, for example, to their clients?

In part, yes. When you have a contract with a client, it is not easy to convince them because it may increase costs or change the project so much that they get scared. Events like the Triennale are ideal in this respect because they do not suffer from market pressure; they are free in every sense of the term. If I dedicate my time to such an event like this it is to try to educate society in a way that I can’t in schools, for example. I believe we have a duty to do so.

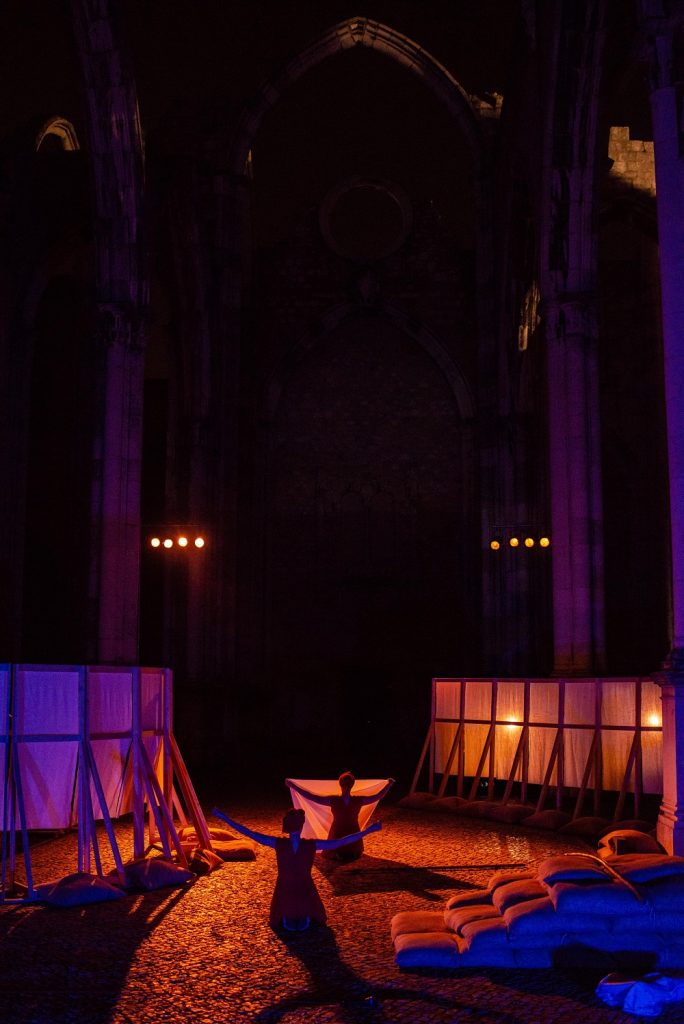

How wild the Greeks were when, driven by pride and greed, they destroyed Troy. The wounds of the long war, which the invader won with a wooden horse, are now in blood in the hearts of Trojan women, to whom Hecuba, “the once celebrated Queen of Troy, ” gives voice: “I have lost everything: my country, my children, my husband.”

Treated like spoils of war, Trojan women await the fate that the gods (and the Greeks) have in store for them: slavery. It is their drama, among the physical and psychological ruins inflicted upon them, that makes “Troianas” a tragedy of women that more than two millennia after Euripides had written it, remains the canonical text of anti-war theater.

“Our decision of adapting this text for the stage was taken about four years ago and it is quite natural that the whole situation that was lived and, unfortunately, persists, having even worsened, has weighed in the choice,” says António Pires, recalling the rise to power of Donald Trump, the wars in Syria and the Maghreb countries and, consequently, the migration crisis that triggered a succession of tragedies.

All this “social and political component” is enclosed in “Troianas,” which, now, through a new translation by Luísa Costa Gomes (made from George Theodoridis’s English translation and later revised with Tim Eckert from the Greek), has been made into a “simpler, more straightforward classical piece.” This is, by the way, one of the virtues that Pires emphasizes in this version, which allows the public to “fully visualize each word and very easily grasp the ideas of the author.” Although, as Luísa Costa Gomes points out in the information sheet, Euripides was “an author very little given to ornaments. Nor would such decorations be desired on such painful subjects.”

In a play in which the main protagonists are women, António Pires wanted to reunite some of the actresses with whom he works regularly and greatly admires. In addition to Rueff, the director gave Alexandra Sargento the role of Cassandra, and Sandra Santos the role of Andromache. The young actress Vera Mora, who works for the first time with Pires, plays the beautiful and treacherous Helen of Sparta.

As for the choice of Maria Rueff for the role of Hecuba, the director highlights “the unparalleled ability of comedians to perform tragedy. And Maria has it all: she has the strength, the nerve and the energy that drives the character to always be on edge.”

On stage until August 17, ” Troianas” also has interpretations from João Barbosa, Hugo Mestre Amaro, Francisco Vistas and finalist students of the representation course of the ACT-Escola de Atores.

Recorded in just two nights, January 7th and 8th, 1969, Com que Voz [With what Voice] took 14 months to reach the public, although the genius of a work that will be forever marked in Portuguese music as the happiest meeting of Amália’s voice and Alain Oulman’s music was never in question. Frederico Santiago writes in his booklet accompanying this new edition of the album, these were “two triumphant nights”, the “apogee of others, where a miraculous culmination was prepared (and conquered)”.

The 12 songs that make up the original album (all with poems by the great names of Portuguese poetry, from Camões to David Mourão-Ferreira, Ary dos Santos, Alexandre O’Neill, Pedro Homem de Melo, Cecilia Meireles and Manuel Alegre), this edition joins the unforgettable ensemble of the original album’s nine tracks entitled Com que Voz, as Amor sem casa (with a poem by Teresa Rita Lopes, believed to have been written with the album in mind, although not in its alignment), Amêndoa Amarga (an unreleased version of 1969, year of recording) or the virtually unknown four-guitar version of Cravo de Papel (poem by Antonio de Sousa).

But this Com que Voz 2019 holds more and more vibrant surprises, namely the first version of Trova do Vento que Passa (only played by Fontes Rocha and Pedro Leal, and reportedly the one that pleased Oulman most) or the “only alternative take that survived” of Madrugada de Alfama. As if these and other treasures were not enough, this edition includes an excellent essay by the classical pianist Nuno Vieira de Almeida where, after a detailed analysis theme by theme, we conclude that we are looking at a perfect record.

In the year that marks 20 years since the death of unparalleled Amalia and preceding the centenary of her birth, Com que Voz returns to stores in CD edition (coming soon, also on vinyl) and made available on digital platforms Apple music, Spotify and YouTube.

How did you get started in design?

I started graphic work at the age of 15 when I was an industrial lithographer. I attended the School of Decorative Arts António Arroio and dedicated myself professionally to creativity in what concerns the general profession of domestic utilities and techniques of general use. I gradually entered this graphic work and the first works I did, still in Portugal, were visual communication logos that identified companies.

Is that the material that is shown in the Fernando Lemos Designer exhibition?

Yes. The thematic agenda of this exhibition is all about that. This is the first show dedicated specifically to my work as a graphic artist or designer. The idea came from MUDE, and I’m very happy that it’s happening in Lisbon. We have been working on this exhibition since 2017, the year in which the director of MUDE, Barbara Coutinho, invited me. The catalog, which is actually a book, is co-edited by MUDE and Imprensa Nacional – Casa da Moeda. The museum also endorsed a documentary about my work, which is being done by Miguel Gonçalves Mendes and Victor Rocha.

Apart from the exhibition, are there more initiatives concerning your work?

Galeria Ratton and Galeria 111 decided to join this initiative and organize two other exhibitions. Ratton will exhibit my work in tile, for which I made new designs. Galeria 111 shows the latest drawings and watercolors and my photographs from the surrealist era. The Imprensa Nacional – Casa da Moeda will also launch a book of my photographs that includes some unpublished ones.

It is inevitable to ask a question about the Azevedo-Lemos-Vespeira exhibition that in 1952 provoked great controversy and scandal, dragging crowds to Chiado. Can you remember what Lisbon was like at the time?

Our Lisbon had several faces but, in a way, we consideredArmazéns do Chiado the only authentic one. It was a provincial Lisbon, and so it remained for a long time. Our exhibition has, to some extent, breached this Lisbon provincialism, kind of snobbish at the same time, having as an image the poor middle-class pattern of Armazéns do Chiado, where we got inspiration from the manikins themselves and from which we made emblems. But that Lisbon was a difficult place for us because censorship was greater than all that. Art was provided by the SNI (National Information Office) where we had no participation. That is why I considered the Lisbon of those times as the city where the Portuguese were leaving. A city solely with automobiles and offices. A city which the 25th of April came to change. It will be great to return to Lisbon so many years later and feel it very different than from before.

As that reality led you to define yourself as “another Portuguese looking for something better”?

Precisely. I left Portugal in the 50s because I did not want to be one more victim of the fascist dictatorship. I left because I was being chased. The phrase you quoted refers to that time and that reality.

In that exhibition in Chiado you presented a set of photographs, now famous, that through an overlapping technique produced formal surrealism recomposition. How did they come about?

Within the surrealist camp, no one was very interested in using photography. I tried to capture, through a hidden vehicle like photography, the face of the Portuguese people because I thought there was nothing that had shown us the face of our people. The first photographs focused on the faces of my friends within the group.

At this distance, what do you think has been the most important legacy of the surrealist movement?

Surrealism brought joy to a post-war period and had the advantage of being the only territory where dreams spoke the truth. It came about to promote the unveiling of reality. Reality for us does not exist. What exists is what we put into it again everyday. A new trend brought about this unveiling of the concealment that is life and that in some places is a political form of organization to take power. Surrealism seems a lie and it is, as all art is a lie.

In 1952 you decide to leave for Brazil.

I did not come to Brazil to stay. I stayed because I liked it and I adapted. First, I was in Rio de Janeiro and then I settled in São Paulo. In Portugal, freedom was the most difficult thing to get in an authoritarian country where I had felt cloistered since childhood. Here I became free. And it was here that I developed my work as an artist and designer. I did a little bit of everything in terms of graphic design: I created brands, magazine covers, posters, illustrations; in short, everything related to visual communication. I had in São Paulo an industrial design office where I launched a children’s literature publisher, 35mm video collage for marketing and business communication, book covers and posters, films, fabric and tile printing, panels for the metro, exhibitions and commercial spaces, institutional walls for building construction, murals. I drew exhibitions, I did many poetry illustrations and advertisements for various public agencies, tapestries… I also collaborated in ABDI’s foundation—the first Brazilian Industrial Design Association—and I was a teacher and cultural manager. But you know, I kept working from time to time in Portugal. For example, for several years I collaborated with my great friend José-Augusto França in the magazines Arts Colloquium and Letters Colloquium,making illustrations and giving news of culture and arts in Brazil. I remember it was for Colloquium that I wrote a piece about Joaquim Tenreiro. That’s all I’ve been seeing in boxes and crates in my house for the past two years, and it will be displayed in Lisbon at this exhibition, according to the curatorial look of Chico Homem de Melo and the exhibition design of Nuno Gusmão, two graphic designers by training. One Brazilian, the other Portuguese…

What else changed with your going to Brazil?

There was a great change in the sense that I became free, I became someone else. Brazil is a country of creativity. The way they speak is, in itself, creative. This insistence saying it is the same language is not true. In Brazil there is no language, there is communication. It was in Brazil that I learned to distinguish the face of the Portuguese people from that of Brazilians, and this influenced my creative method. Creation does not happen by chance. It happens because of the culture we live in and, here, a lot of people helped me make sense of what I hadn’t understood.

You say that you are always a designer in everything you do. Could you elaborate on that?

I say that because I’m very graphic. I make everything with a graphic vision. I understand design as the psychoanalytic study of dreams. Design is what happens, not just what is thought. Design is not synonymous with drawing. It is an idea that takes the specific shape of the content. It is the intention of an idea.

The Lisbon Festivities officially open at 7:30 p.m on June 1. In Alameda D. Afonso Henriques in the direction of Fonte Luminosa, Tatiana-Mosio Bongonga, currently one of the world’s greatest tightrope artists, will walk 300 meters on a tightrope at a height of 33 meters. In Linhas Voadoras, the acrobat co-founder of Companhia Basinga (France) and her peers will challenge gravity, accompanied by live music from the Armada Band.

As the Festivities begin on World Children’s Day, it is worth highlighting two activities for the young: in Jardim da Quinta das Conchas, Guardar Segredo invites children to enter two wardrobes to discover the most secret of secrets in a show forming part of the commemorative program for the 125th anniversary of São Luiz Theater; while elsewhere in the city, to be precise, in Calçada da Ajuda, LU.CA – Luís de Camões Theater celebrates its first anniversary with various shows, street performances, artistic expression workshops, readings and other surprises.

The traditional popular procession, floats, displays and marriages of Saint Anthony return to the streets. On the longest night of the month (June 12), 16 pairs of newlyweds, 23 procession participants and 1 guest party, the Marcha Popular de Ribeira de Frades, will parade down Avenida da Liberdade under the aegis of the popular Saint.

Speaking of weddings, the now customary program Fado no Castelo proposes an unlikely coupling: singers of the “Fado” tradition, Ana Moura and Raquel Tavares, will “marry” this type of song with other musical styles. On June 14, Ana Moura will accompany the traditional a capella music of the group Sopa de Pedra; the following night, Raquel Tavares will perform with the black gospel music of the Gospel Collective.

Among several dozens of proposals, Festival highlights include another edition of the Com’Paço festival, which once again presents philharmonic bands from all over the country in two city gardens, including for the first time Alameda D. Afonso Henriques, which will be the stage of the closing concert featuring the young musical band Com’Paço’19 and Anabela as guests (June 22). Also highlighted are the intercultural Lisboa Mistura, which this year moves to Quinta das Conchas (June 8-10), and the Diversity Festival in Ribeira das Naus (June 29-30).

To conclude, on June 29, in Torre de Belém Garden, the closing is marked by a unique concert put together especially for the occasion dedicated to Antonio Variações who in 2019 would have turned 75 years of age. His songs will be recreated on stage by Ana Bacalhau, Conan Osiris, Lena D’Água, Manuela Azevedo, Paulo Bragança and Selma Uamusse, accompanied by the Orquestra Metropolitana de Lisboa and symphonic arrangements by Filipe Melo, Filipe Raposo and Pedro Moreira.

The full program of Lisbon Festivities can be found here.

The festival’s masked men come from afar – from the north of the Iberian Peninsula, central Portugal, Italy, Hungary, Colombia, and Macao – to celebrate a tradition whose origins are lost in time, a time when men lived in harmony with nature. In Portugal, it is mostly in Trás-os-Montes that the memory of these ancient rites – celebrated during the Winter Festivities, which begin with the Winter Solstice (December 21) and run until Shrovetide – is kept alive. In these festivities, which merge pagan and Christian elements, masks take center stage. Behind them are men who in days of yore had to be single, thus replicating initiation rituals or ceremonies of purification, fertility, and fecundity. Nowadays, due to the exodus and aging of rural communities, rules have changed and all men can take part in these rituals. Dressed in colorful woolen costumes and terrifying masks – which, in some cases, are passed down from generation to generation – these men run through the streets to the sound of bagpipes and cowbells. They take on the role of otherworldly creatures who, in a complex world made up of rites, magic and symbolism, would purge the evils of the community. See them in all their splendor.

‘Caretos’ of Grijó (Bragança)

‘Caretos’ take the streets of Grijó da Parada during the Feasts of St. Stephen, the patron saint of boys (December 26-27). The rituals probably date back to the Celtic era, and are led by the ‘King’ and the ‘Bishop’. With their bright, colorful woolen garments, where red predominates, and their brass masks with protruding tongues, they entertain the audience with shouts, jumps and the sound of cowbells, whose number varies according to the richness of the costume. They carry a staff that is used to discipline the audience and a pig bladder which, according to some scholars, suggests fecundity.

‘Máscaros’ of Vila Boa (Vinhais, Bragança)

‘Máscaros’ of Vila Boa (Vinhais, Bragança)

Originally, they would take the streets on the occasion of the Feasts of St. Stephen. Now it is during Mardi Gras that small groups of masked men ‘attack’ neighboring villages in search of their ‘victims’ – single girls. Known as ‘cochalhadas’ (from ‘chocalhos’, or ‘cowbells’), these ‘assaults’ on women used to have a sexual purpose, associated with fecundation. For this reason, in days of yore, young girls would watch the festivities from the window, while married women would be barred from going out by their husbands. Bedecked with fringes, the colorful woolen costumes of Vila Boa’s ‘Máscaros’ contrast with their devilish masks, which are knife-carved out of chestnut wood or tinplate.

‘Caretos’ of Podence (Macedo de Cavaleiros)

‘Caretos’ of Podence (Macedo de Cavaleiros)

They stand out for their red tinplate masks, tricolored woolen costumes (yellow, green, and red) and hood, which features a braid (the ‘tip of the tail’) that is used for whipping young girls. They brighten Podence’s ‘Entrudo Chocalheiro’ (‘Cowbell Shrovetide’), which is considered the most genuine in the country – hence the candidacy to UNESCO Intangible Heritage status in 2018. Characterized by banquets, masquerades and dances, these festivals – which correspond to the Roman Bacchanalia in March – celebrate the ancient connection with nature, agriculture and fertility.

‘Cardadores’ of Vale de Ílhavo (Ílhavo)

‘Cardadores’ of Vale de Ílhavo (Ílhavo)

On Fat Sunday and Mardi Gras, ‘Cardadores’ (‘Cardingers’) emerge from everywhere, heralded by the deafening noise of the cowbells on their waist. As the name implies, this tradition is associated with the carding of wool, which is here transfigured into the ‘carding’ of girls. Preparations for the festival are made by men under great secrecy, evoking ancient initiation rituals. The costume consists of women’s underwear, a ‘tricana’ scarf, socks, and sneakers. The mask, which is highly sophisticated and can weigh up to 5 kg, is made of cloth, cork, bovine mustaches, two bird wings, ‘gazetas’ (ribbons), and candle yarn. All wrapped in Tabu perfume.

‘Caretos’ of Lagoa (Mira)

‘Caretos’ of Lagoa (Mira)

Lagoa is the only place with ‘caretos’ in the municipality of Mira. Their Mardi Gras parades are an ancient tradition, but its exact origin is unknown. Yet its connection with pagan initiation rituals into adulthood seems indisputable. Known as ‘campinas’, the painted masks of these ‘caretos’ are bedecked with animal horns and skin. They wear red skirts, which evoke sin, and a white shirt, symbolizing purity. They carry the mandatory cowbells in leather straps.

Los Carnavales de Villanueva de Valrojo (Zamora)

Los Carnavales de Villanueva de Valrojo (Zamora)

Due to its ancestry and originality, the Mardi Gras of Villanueva de Valrojo has attained great fame in the Spanish province of Zamora. The festivities evoke ancient pagan rites of purification and fertility. Masked men wearing colorful costumes and masks (made of plastic, cork or copper) chase girls through the streets with their long pincers.

“Without a long-term partner like the Maria Matos Theater and with São Luiz celebrating 125 years, this entire edition of FIMFA was a huge challenge for us as programmers”. Luís Vieira and Rute Ribeiro, directors of the Tarumba-Teatro de Marionetas, underline this conjuncture to explain much of what is the programming behind this edition of the most important puppet festival in Lisbon, which, almost celebrating 20 years, relies heavily on street shows, especially in Castelo de São Jorgea place that will be the stage of “an almost mini-festival” that will “have proposals that have never been possible to present at the festival”.

Another great offer of this edition is a complete “radical programming”, in the words of the couple, especially reserved for families. Lisbon now has a theater for children and a youth audience, the LU.CA – Luís de Camões Theater, and this opportunity could not be lost.

On the fringes of these axes, we challenged Luis Vieira and Rute Ribeiro to make the difficult choice of six spectacles considered as absolutely not to be missed in this 19th edition.

FIMFA Lx19 – Festival Internacional de Marionetas e Formas Animadas

★ Vem aí o FIMFA!! ★ #FIMFA Lx19 – Festival Internacional de Marionetas e Formas Animadas???International Festival of Puppetry and Animated Forms9 a 26 de Maio -9 to 26 May – #LisboaConsulte o programa em * Check out the programme: www.tarumba.ptEspaços de apresentação: CASTELO DE S. JORGE, São Luiz Teatro Municipal , @Teatro Nacional D. Maria II, @LU.CA – Teatro Luís de Camões , Teatro do Bairro, Teatro da Trindade, Teatro Taborda – Teatro da Garagem, @Museu de Lisboa – Palácio Pimenta, Cinemateca Portuguesa-Museu do Cinema, @Museu Nacional do Teatro e da DançaVídeo de / by Flúor#fimfa19 #fimfalx19 #fimfa2019#tarumba #marionetas #puppets #puppetry #puppetfestival #fimfalx #titeres #figurentheater #marionnettes #marioneta #atarumba #festival #Lisbon

Posted by A Tarumba Teatro Marionetas on Monday, 6 May 2019

Hans Christian, you must be an angel

Teatret Gruppe 38 (Denmark)

Teatro do Bairro, 10th to 12th May

A memory of Hans Christian Andersen. The audience will be greeted by two butlers and experience all the magic that 20 characters created by the Danish author offer around a table. It’s an absolutely stunning show… Certainly, Hans Christian himself would be fascinated if he could watch it.

Vu

Cie Sacékripa (France)

Teatro Taborda, 10th to 12th May

It is almost a spectacle of a new miniature circus. Wordless, with lumps of sugar, a coffee machine or a cup of tea, Etienne Manceau will make us think about our lives, about our daily lives. A true gem in the programming of FIMFA.

Portraits in Motion

Volker Gerling (Germany)

Teatro do Bairro, 14th and 15th June

Gerling is a German director and photographer who fell in love with flipbooks. The genesis of this show is in his itinerant journey through Germany, which the artist traveled furnished with flipbooks with his own photographs, which he showed as if it was an itinerant exhibition. From here, he has been photographing people and listening to stories, reproducing many of them in this award winning show that will make us laugh but also stir emotions.

Chambre Noir

Plexus Polaire (France/Norway)

Teatro do Bairro, 17th to 19th May

The work of the Plexus Polaire and its creator Yngvild Aspeli has been closely followed by us in recent years. On this return to FIMFA, Aspeli uses human-size puppets, video and live music to tell the story of Valerie Jean Solanas, the woman who tried to kill Andy Warhol. It’s an amazing show, one of those which we can’t miss because of the way it speaks to us, capable of transporting viewers to the golden years of Factory, Warhol’s studio in Manhattan.

A Filha do Tambor-Mor

Operetta by Jacques Offenbach (Portugal)

São Luiz Teatro Municipal, 22nd to 25th May

This great production of São Luiz gives us a particular pride, since A Tarumba takes in the set design and the puppets. It is the comic operetta that inaugurated the Theater 125 years ago, and on the account of it we formed a team of collaborators, specialists in the most diverse areas. On stage there will be an almost full size donkey, Martin; an order box animated by dancers; Italian period paintings that come to life; and even a madonna coming down from the pulpit, and… it’s better if we don’t reveal anything else! In short, an entertaining operetta with well-defined “marionette” outlines.

A Filha do Tambor-mor – ensaios cenografia

É de revirar os olhos, a cenografia de A Filha do Tambor-Mor, J. Offenbach #saoluiz125anos!www.teatrosaoluiz.pt/espetaculo/a-filha-do-tambor-mor

Posted by São Luiz Teatro Municipal on Friday, 3 May 2019

Vies de Papier

La Bande Passante (France)

São Luiz Teatro Municipal, 25th and 26th May

It is a kind of documentary object theater. The authors bought a photo album at a flea market and decided to look for the stories of the people portrayed there. The interest about the family’s journey back to the days of Nazism leads them to a work of theater archeology where research will confront the “investigators” themselves with their personal and family lives. It is an exciting journey, a fantastic trip to a world of others that is, inevitably, ours too.

Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen was one of the greatest names of 20th-century Portuguese language poetry, cultivating, according to António José Saraiva and Óscar Lopes, “through classic Mediterranean images, the identification of the eternal with human reality and its aspirations to justice.” The remains of the writer rest in Panteão Nacional (Portugal’s ‘National Pantheon’), not far from the house where she lived, on Travessa das Monicas no. 57, just a few steps from Graça Lookout, which is now named after her and features her bronze bust, carved by sculptor António Duarte. Reality confirms Sophia’s verses: “Even if I die the poem will find / A beach where to break its waves.”

Throughout the year the Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen Centennial Committee, headquartered at Centro Nacional de Cultura, offers a rich program to celebrate the centenary of the birth of this “great poetess and exemplary moral, civic and cultural figure who inspires, awakens, challenges and renews us,” as the Manifesto endorsed by the Committee reads.

The program before summer includes: an evocation of Sophia at the Palácio de São Bento Gardens on the occasion of the April 25 Revolution commemorations; an afternoon of debates followed by the reading of Sophia’s poems on Fernando Pessoa (April 30 at 3 pm in Museu de Lisboa – Palácio Pimenta); an exhibition of Vieira da Silva and Arpad Szenes’ works in Sophia’s private collection, to be held at the artists’ Museum/Foundation in Largo das Amoreiras; a two-day conference at Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, featuring the greatest Portuguese and foreign experts on Sophia’s work (May 16-17); and a concert by Orquestra Sinfónica Juvenil which will include the premiere of a Christopher Bochmann piece for choir and orchestra based on a poem by Sophia.

For more details about the commemoration program, visit the Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen Centennial website .

If you’re a fan of “heavy music,” Restelo Stadium will host, in early July, VOA – Heavy Rock Festival, headlined by Slipknot on July 4 and by Slayer on the following night.

One of the year’s major music festivals – NOS Alive– will also be held in July, at Passeio Marítimo de Algés. There are lots of big names and it’s hard not to get excited about the line-up. British band The Cure will set the bar high on the first night (July 11). Portuguese outfits Ornatos Violeta and Linda Martini will also perform on that day. Vampire Weekend are the headliners on July 12, and The Smashing Pumpkins, The Chemical Brothers and Thom Yorke will close the festival with a bang on the last day.

This year, from July 18 to 20, Super Bock Super Rock will return to Meco. The first day features Lana del Rey but also the controversial Conan Osiris. On July 19 you can see Phoenix or Charlotte Gainsbourg, while Janelle Monae and Rubel are the headliners for the last day.

Still in July, Cascais hosts EDP Cool Jazz, to be held from July 9 to 31. The lineup consists of mostly jazz-related names – such as Jamie Cullum, Diana Krall or Jacob Collier – but also includes shows by The Roots, Tom Jones, Jessie J and Kraftwerk, as well as Portuguese outfits HMB and Best Youth. Another edition of Sol da Caparicahas also been confirmed, but the dates and artists are yet to be announced.

For a more urban experience, Lisbon will host, as usual, another edition of Jazz em Agosto at Gulbenkian, Jazz im Goethe Garten at the Goethe-Institut, or Somersby Out Jazz, which brings good music to various parks across the city.

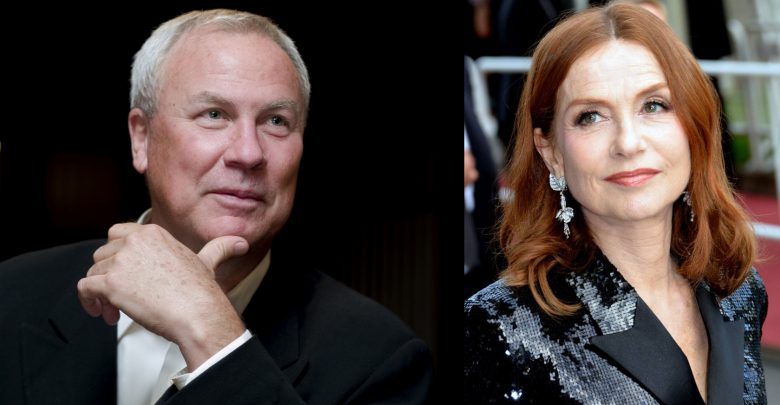

With a world premiere scheduled for the Espace Cardin in Paris on May 22 of Mary Said What She Said It’s a monologue written by the African-American writer Darryl Pinckney, a recognized author in the theater world for his collaborations with Robert Wilson. In fact, this is an even broader reunion, since the acclaimed French actress Isabelle Huppert will join them more than 20 years after this “glorious” trio brought another monologue to the stage: Orlando, from the Virginia Woolf novel.

As Pinckney himself points out, “the ever inventive Robert Wilson offers to the great Isabelle Huppert the throne of Queen Mary of Scotland, the monarch who, because of her passions, lost her crown.” A three-act play, Mary Said What She Said It’s a story of love, power, and betrayal of a woman who exemplified the irrepressible desire for freedom. Huppert’s talent, therefore, is to be measured to the full extent of her talents.

In a production at the Theater de la Ville (directed by Luso-French Emmanuel Demarcy-Mota), not only does Wilson shine on stage, but the show’s stage set and lighting does as well. It also features original music by the famous composer Ludovico Einaudi and costumes by Jacques Reynaud.

The show is part of the 36th edition of the Almada Festival that runs from July 4 to 18 in Almada and Lisbon. The tickets, as well as the signatures that give access to all the shows at the festival, will go on sale later this month.

paginations here